The festival of San Fermín takes place annually in Pamplona, Spain, between July 6 and July 14. The most (in)famous event of the festival is the running of the bulls (Spanish, encierro) that takes place each morning.

Bob and I plodded into town on July 1, five days early.

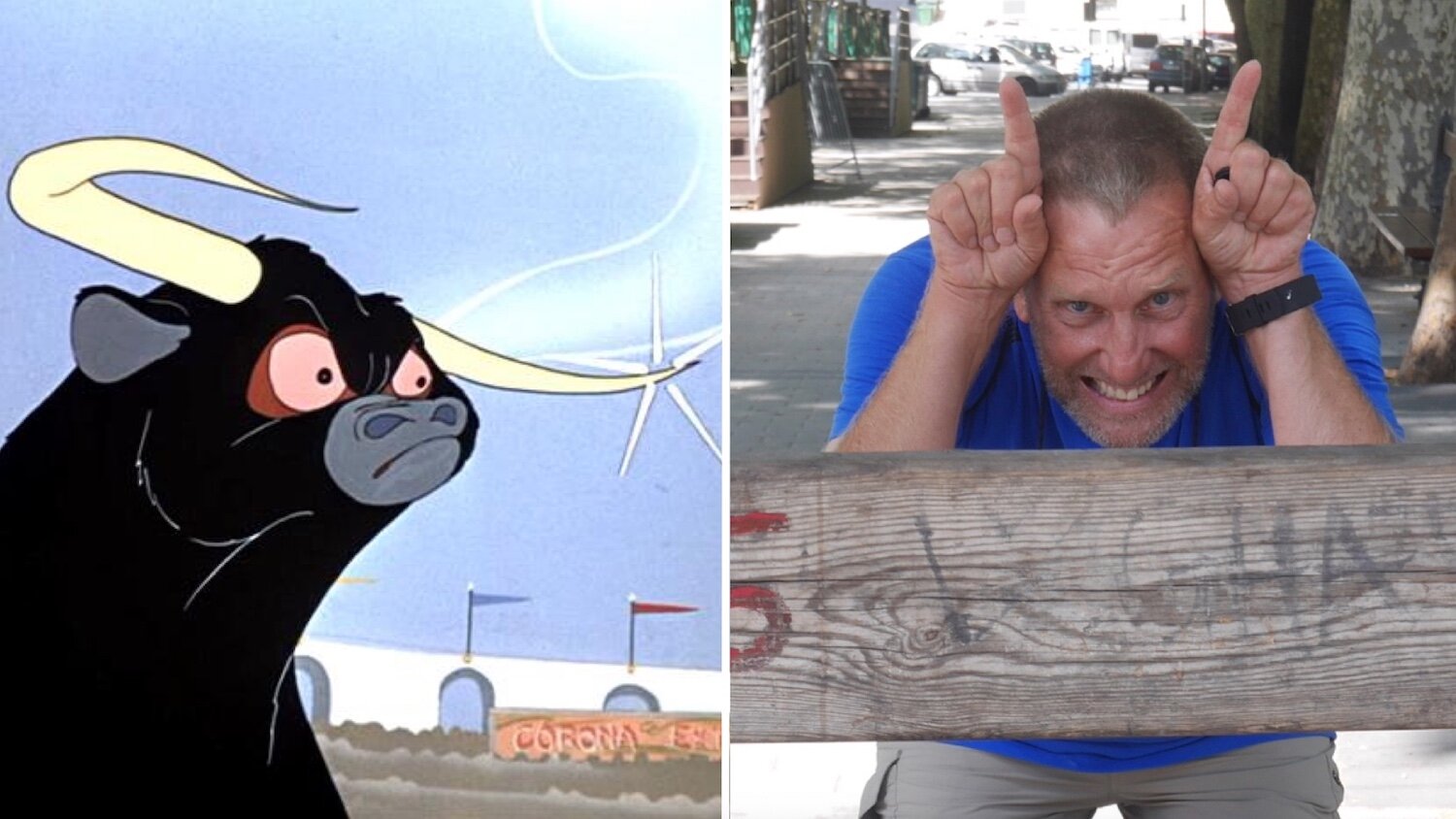

Bob studies the advertisement.

In retrospect, it was probably best. My springs aren’t what they used to be. And with a million visitors (in a town of 200,000), lodging is impossible, prices are outlandish, and most who attend the festival do so for reasons that have less to do with the virtues of the patron saint of Pamplona* and more to do with the mix of blood-sport, alcohol, and machismo. It’s a wicked combination, much like college administration.

The running of the bulls is a 400-year tradition that is believed to have started with the transport of fighting bulls from the field to the arena. As the beasts were driven into town, young men attempted to sprint ahead of them, run among them, or even jump over them. It is a dance with death that continues to this day.

A modern Spanish fighting bull is a thousand pounds (or more) of muscle, tipped with horns. It can run up to 35 mph, turn on a round peseta, and is bred to encourage strength and stamina. The toro bravo—“angry bull”—is raised in isolation to encourage aggressiveness. It may not be as heavy as other bulls, but is more ripped. Think bovine olympian.

The Spanish fighting bull is ripped and tipped. Image from here (accessed 10/8/2021).

After being driven through town, the bulls (and occasionally a horse or a matador) are killed in the ring with all the cultural pageantry of the corrida de toros.

It is a primal and deeply human activity.

I remember a visit to Heraklion Archaeological Museum in Crete a few years ago. I stood before a restored fresco panel excavated in the Minoan palace at Knossos. Pictured are three youths cavorting around an huge bull stretched out in frisky gallop. One grips the animal by the horns. Another flips breathlessly over its back. A third appears to be sticking the landing in the wake of the charge. Keep in mind that this mad Mediterranean act is older than Moses.

Young Minoans demonstrate the art of bull leaping. Risk it for the biscuit? Image from here (accessed 10/8/2021).

Back in modern Pamplona, the runway to the bullring used in the encierro is fixed. It measures about 875 meters in length and has three corners (one is nicknamed, “Dead Man,” as the bulls can lose their footing and crash into the barricade). The first 200 meters or so are a slight uphill, giving every advantage to the animals as they blast out of the start, terrorized by fireworks and a screaming crowd.

I fiddle with the math. How long would it take me to cover 800 meters? How long would it take the bulls? How much lead would I need before being overcome by the herd? How about the people clogging the way in front of me? No, no! That’s sheer madness!

A wooden fence keeps the action focused. Gaps are wide enough, to allow for emergency exits.

At the time of our arrival in Pamplona, much of the barrier had been assembled. Each timber was numbered to make the process of set-up and break-down easier.

Bob and I followed the fencing to the bullring. The metal doors were locked. But there was a keyhole. We peeked through and saw the sun shining on the arena floor inside. It was the closest I’ve been to a functioning Roman amphitheater.

The wooden fence leads the runners from the streets to the bullring. Here at a place known as the Callejon the route narrows to only 3.5 meters. Even though the bulls have slowed by this point, it is still quite dangerous because of the compression. Runners and bulls pile up trying to squeeze through the gap.

The running of the bulls was immortalized by Hemingway in his The Sun Also Rises. Standing before the red door of the bullring is the appropriate place to consider one passage. It comes from the perspective of the protagonist Jake Barnes.

“The stretch of ground from the edge of the town to the bull-ring was muddy. There was a crowd all along the fence that led to the ring, and the outside balconies and the top of the bull-ring were solid with people. I heard the rocket and I knew I could not get into the ring in time to see the bulls come in, so I shoved through the crowd to the fence. . . Then the people commenced to come running. A drunk slipped and fell. Two police-men grabbed him and rushed him over to the fence. The crowd were running fast now. There was a great shout from the crowd, and putting my head through between the boards I saw the bulls just coming out of the street into the long running pen. They were going fast and gaining on the crowd. . . . There were so many people running ahead of the bulls that the mass thicked and slowed up going through the gate into the ring, and as the bulls passed, galloping together, heavy, muddy-sided, horns swinging, one shot ahead, caught a man in the running crowd in the back and lifted him in the air. Both the man’s arms were by his sides, his head went back as the horn went in, and the bull lifted him and then dropped him. The bull picked another man running in front, but the man disappeared into the crowd, and the crowd was through the gate and into the ring with the bulls behind them. The red door of the ring went shut.”

The bull ring of Pamplona was inaugurated on 7 July 1922. Image from here (accessed 10/7/2021).

Five days before the festival of San Fermín was a good time to be in Pamplona. It gave us four days to get out.

¡Buen Camino!

Hmmmmm.

*Saint Fermín was a Christian who was killed in a Roman persecution. One story of his martyrdom suggests that his feet were tied to a bull and he was dragged to death. This act, in part, stands behind Pamplona’s running of the bulls.

For details and a correction to this legend, see the post here (accessed 10/7/2021).

This bronze bust of Hemingway was executed by Luis Sanguino in 1968. It stands on the sidewalk just outside Pamplona’s bull ring.

For future Bible Land Explorer trips (that do not include the encierro), see the website here.